Bernardo Luis Tacón y Hewes

Duke of La Unión de Cuba

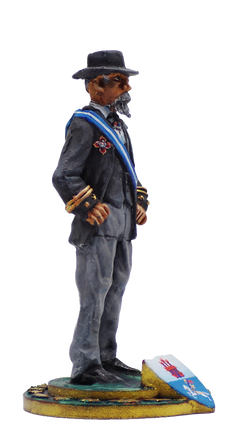

Bernardo Luis Tacón y Hewes (England, 1844 - Madrid, 15 February 1914), 3rd Duke of the Union of Cuba, 2nd Marquis of Bayamo, Grand Cross of Naval Merit, Gentleman of the Chamber with exercise and servitude, Senator of the Kingdom. Son of Miguel Tacón y García de Lisón (1809-1869), 2nd Duke of the Union of Cuba, 1st Marquis of Bayamo, minister plenipotentiary and senator of the kingdom, and Francisca de Sales Hewes Kent (d. 1888). He married Matide Calderón y Vasco in first marriage on 8 January 1871 and in second marriage on 8 May 1912, in Madrid, to María Carlota Beranguer y Martínez de Espinosa (b. 1858). On 29 May 1914 he was succeeded by the son of his first marriage, María Carlota Beranguer y Martínez de Espinosa (b. 1858). On 29 May 1914 he was succeeded by the son of his first marriage, María Carlota Beranguer y Martínez de Espinosa (b. 1858).

The mambises were the guerrilla independence soldiers who fought for Cuba's independence from Spain in the Ten Years' War and Cuban War of Independence. According to Cuban writer Carlos Márquez Sterling, "mambí" is of Afro-Antillean origin and was applied to revolutionaries from Cuba and Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) in the 19th century. The surviving Spanish soldiers, who had been fighting in Santo Domingo, were then sent to Cuba once the Ten Years' War broke out in 1868. These soldiers, noting the similar tactics and machetes use by the Cuban independence fighters as by the original “men of Mamby”, began calling the Cuban independence fighters mambises. Though this was meant as a derogatory slur towards the Cuban rebels, the Cubans accepted and started using the name with pride. Other sources cite the term to be of Congo origin or, as stated by Esteban Montejo in Biography of a Runaway Slave, mambí refers to the child of a monkey crossed with a buzzard. The mambí soldiers made up most of the National Army of Liberation and were the key soldiers responsible for the success of the Cuban liberation wars. They consisted of Cubans from all social classes including white Cubans, free black people, slaves, and mulattos. During the Ten Years' War, slaves were promised their

freedom if they assisted the Creoles in the fight against the Spanish. The freeing of slaves to help fight was started by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. At the end of the war, even though independence from Spain was not achieved, Spain agreed to honor the freeing of the slaves who had fought against them. The mambí forces were made up of volunteers who mostly had no military training and banded together in loose groups who acted independently to attack the Spanish troops during the Ten Years' War. It is estimated that 8,000 poorly armed and underfed mambises inflicted close to 20,000 casualties on the well-trained Spanish soldiers during the Ten Years' War. Similarly, by the end of the War of Independence the National Army of Liberation numbered nearly 50,000 of which only about 25,000 were armed. The leaders, having learnt from previous mistakes, had organized the army into “6 corps with 14 divisions, 34 brigades, 50 regiments of infantry and 34 cavalry.” Even though, once again, they were limited on resources, they possibly inflicted 71,000 casualties out of the 250,000 Spanish troops sent to the island. Mambí independence fighters were not limited to men. During the War of Independence, Spanish general General Valeriano Weyler Nicolau initiated "Reconcentración" which forcefully moved rural inhabitants into the cities in makeshift concentration camps. Conditions in these camps resulted in mass starvation, disease, and large numbers of deaths of the Cuban population. The prospect of these conditions pushed many families, including the women and children, into joining the independence movement. The best known mambí woman is Mariana Grajales Cuello, who was Antonio Maceo Grajales’s mother. Mariana and all of her sons participated in all three of the wars of independence. Prior to the Ten Years' War, private ownership of weapons was allowed but, considering that at this time many of the black were still slaves, most of the men who became mambises did not have firearms. Following the war, Spain prohibited ownership of firearms in an effort to prevent another uprising. In both cases, the lack of firearms forced the mambises into using what they had: machetes and sometimes horses. At the start of the Ten Years' War, Máximo Gómez, who had been a cavalry officer in the Spanish Army, taught the men the "machete charge". This became the mambises' most useful and feared tactic in both wars. These methods resulted in Guerrilla type warfare that favored them due to the element of surprise and their knowledge of the terrain and environment. Knowing additional weapons were needed, numerous attempts were made to procure arms from outside the country. During both wars of independence, many expeditions were funded to bring equipment and volunteers for the Liberation Army. During the 1895 War, 96 armed expeditions landed in Cuba. Despite this interference, and having only originally started with a small number of weapons, the mambises were able to build up a significant arsenal by conducting raids on the Spanish troops and strongholds.

The Marquisate of Bayamo is a Spanish noble title created on 17 September 1847 by Queen Isabella II of Spain in favour of Miguel Tacón y Rosique, lieutenant general of the Royal Navy.1 It received the grandeur of Spain on 11 October of the same year. Its name refers to the island of Cuba, at that time an integral part of the Kingdom of Spain. Miguel Tacón y Rosique (Cartagena, 10 January 1775-Madrid, 12 October 1855), 1st Duke of the Union of Cuba, 1st Marquis of the Union of Cuba, Lieutenant General of the Royal Navy, Military Governor of Popayán, Captain General of Andalusia, Cuba and the Balearic Islands, Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece and of the Order of Santiago, Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III and of the Order of San Hermenegildo.

Awards: Star and insignia of the Real Maestranza de Caballería de La Habana, stars of the Cross of Naval Merit (Cruces del Mérito Naval) and the Gentilhombres Grandes de España con ejercicio y servidumbre (Gentlemen of the Bedchamber Grandee of Spain).